Heart of A Champion

Saturday mornings, Kristen Patton puts on her workout gear and drives to a local park to meet up with her personal trainer and a few fellow exercisers for a weekly small-group workout.

Sounds typical enough for an active Austinite, except that Patton is a heart transplant patient, as are her workout companions in the group called Mighty Heart Fitness. Her trainer, exercise physiologist Nixon Williams, specializes in cardiac rehab at Seton Medical Center. The training goal: health and happiness and longevity, of course, but also medals at the Transplant Games — Patton already has five.

Let’s back up.

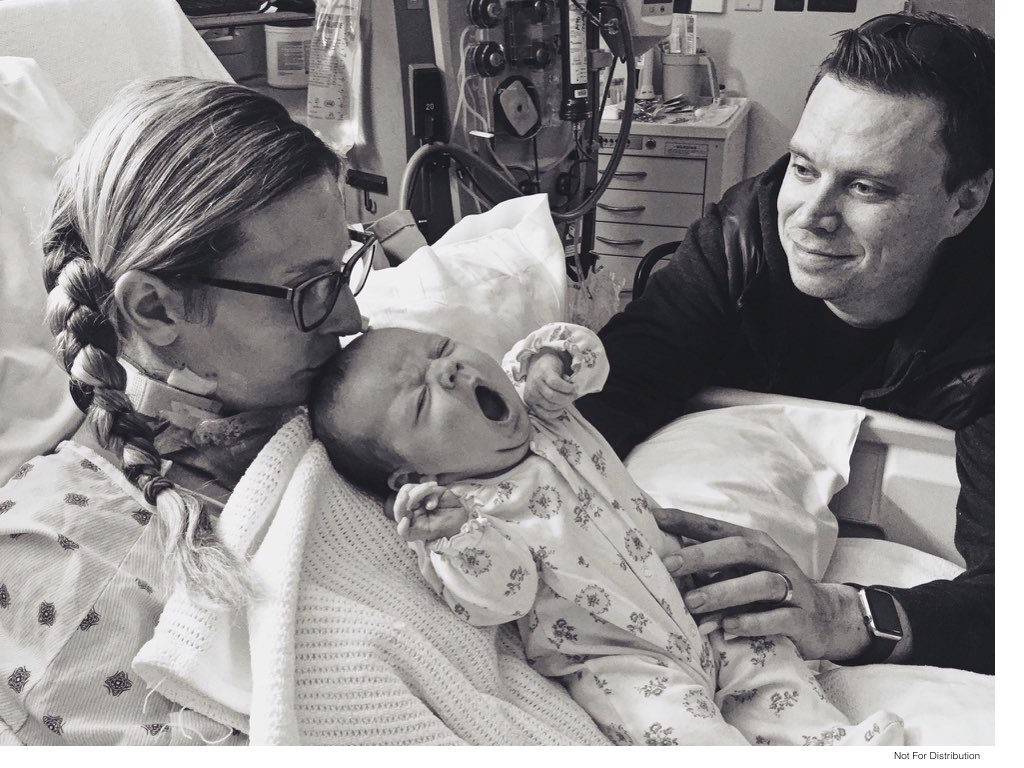

On Christmas Eve in 2015, three days after giving birth to her fourth child, a little girl named Hattie, Patton suffered a heart attack and had to be rushed to the hospital, where she then had a second attack. She went into emergency surgery and didn’t wake up for a month.

Her heart attacks were caused by a rare event known as spontaneous coronary artery dissection, or SCAD, which can happen toward the end of pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Although the link between SCAD and pregnancy is not fully understood, research suggests that the changes in hormones and blood volume inherent in pregnancy could be the cause. According to the Cleveland Clinic, while SCAD can happen in both men and women, SCAD is more common with women, and one-third of SCAD events happen during pregnancy or soon after giving birth.

“When I woke up, I couldn’t even lift my head up. I had no strength, I couldn’t move,” Patton says. “I remember I saw my cell phone, and I wanted to get it to call someone, because I had no idea really where I was or what had happened — I happened to wake up at a point in time when no one was in the room with me — and I remember it was just like right there, and my arm wouldn’t go.”

Before Patton left the ICU, she had multiple surgeries, one which implanted a device called an LVAD to power her heart for her for the foreseeable future.

Her complete loss of strength meant Patton had to start from zero in rehab. She had to build up to sitting, eating solid foods, standing and walking. But all the while, she had the image of her four kids, including little Hattie, still only a few months old, in the back of her head as motivation.

Patton with her daughter, Hattie, while in the hospital.

Patton started working with Williams, as well as the rest of the team of exercise physiologists at Seton’s Cardiac Rehab program, once she returned home from a five-week stint in a rehab hospital post-ICU and began out-patient cardiac rehab. Patton was much younger than the average LVAD patient, and with her four young kids at home, she had things she wanted and needed out of rehab that were different from most of Williams’ other patients.

“The [typical] cardiac rehab training wasn’t going to get me to a point to where I could lift my daughter as quickly as I needed it to,” Patton says. “She was a baby. She was only three days old when I had my heart attack – she would only be little for so long, so it was really important to me that I be able to get down on the floor and pick her up and stand up with my LVAD.”

Patton was also not yet approved for a heart transplant. To get there, she had to get stronger and healthier. So, Williams consulted with Patton’s doctors and found out exactly what he could and couldn’t do with his very driven patient. The pump portion of the LVAD is surgically implanted inside the patient’s body, but a controller and battery pack are worn externally, and everything is connected by cables. That meant there were a lot of things to avoid — anything involving twisting from side to side, which could pull or tug at the cables, and no jumping or even jogging, which would shake the device.

Williams got creative. He and his team brainstormed and modified and put together a program that would challenge Patton, get her to where she needed to be to care for her family and qualify for a heart transplant — all while keeping her safe and as pain-free as possible. They even named a medicine ball “Hattie” and worked on picking it up from the ground and standing up.

“I just kept pushing it,” Patton says, “because what they kept saying to me was, ‘The healthier you get, the happier you’ll be with this device,’ and also at that point, I was not approved for a heart transplant. I knew that getting healthy would be a requirement, and the stronger you go into heart transplant, the more likely you are to have a successful outcome.”

And she did it. First by earning the stamp of approval to be listed for a transplant, and then 11 months after the initial heart attack, getting the call telling Patton they had a heart for her.

Patton walked into the hospital for her transplant feeling good, as good as she has ever heard anyone with an LVAD describe the feeling. Which was very strange — finally back to feeling OK, she voluntarily returned to the hospital where it all began to undergo yet another, even more major surgery.

“There was a lot at work in my life during that time, and I felt very connected to God and very hopeful and optimistic,” Patton says. “It wasn’t necessarily hopeful or optimistic around years and years and years of life on this planet. It was more just I felt very at peace with where my life was. Definitely wanted to fight hard to keep the ability to stay here and raise my children, but also just in awe of recognizing the kindness that exists on this earth and the people that are here.”

Patton’s surgery went well, and thanks to all the work she had done with Williams and the other trainers on the Seton cardiac rehab team and on her own, she recovered very quickly. She left the hospital eight days after the surgery and went to her first post-op cardiac rehab session two weeks later.

As her graduation from post-transplant cardiac rehab approached, Patton frequently probed Williams, saying, “Do you still train clients on the side?” He would always answer no, he was purely working with patients in the hospital, despite having a previous career as a personal trainer. But Patton was persistent, and she kept asking.

Patton with her trainer, Nixon Williams, in the hospital.

“Right before it was time for her to graduate,” Williams says, “I’ll never forget, she said, ‘I found a personal trainer, but she’s more of a powerlifter,’ and when she said that, I said, ‘OK, alright, I’ll help you.’”

Williams started coming to Patton’s house to train her one-on-one. They worked on squats, kettlebell swings, pushups and other movements that would help her in the Transplant Games, which she had been determined to compete in since before she even got her new heart. Back in her LVAD days, she had seen an ad for the Games in the waiting room of her doctor’s office.

“I was like, ‘What? Wait, tell me more, what is this?’” Patton says. “It was just so exciting, because I realized there is this thing that I can strive for, and it’s not just some pass-this-next-medical-exam-type milestone. It’s actually like an awesome, normal-person thing…That gave me more motivation to actually get in shape for the transplant, because I was like, ‘Hey, people who get transplants go and compete in these things.’”

“She’s driven,” Williams says. “[Kristen] works hard, and she wants to become the best that she can because she has little ones. She wants to be there for them, and she knows that exercise is a very important part for her, and so she takes it really seriously.”

Patton, Williams added, claims not to be competitive, but when he would introduce a new movement, he could see her frustration if she couldn’t immediately master it. “That’s OK,” Williams would say. “Maybe it’s my coaching.”

“No,” Patton would reply. “It’s me.” And then she’d work on it on her own all week long, determined to have the movement mastered the next time she and Williams saw each other.

“Nixon and I, through all of that, it wasn’t just working out,” Patton says. “There were so many conversations. I was learning from him, and he was learning from me, and it was helping him be better at treating other patients in his job.”

After they had been training together for a while, and Williams had witnessed Patton’s impressive progress and improved health, Williams said to her, “I think I’d like to expand our group to other heart transplant patients. What do you think?” Patton immediately jumped on board, and they dubbed their group Mighty Heart Fitness.

The group’s numbers have always been small. After all, there are only so many heart transplant patients in the Austin area. But Williams and Patton both remain passionate about the project and keep it going, whether Patton is the only participant in the class or if they manage to round up a few more.

“Everybody that came within the group, they’d say their goal was to catch up with Kristen,” Williams says. “She was the pinnacle of where you wanted to get to, so everybody was in competition to reach where she was at…[Kristen’s] movement, her strength is just really unbelievable in terms of where she’s at right now.”

The group’s purpose goes beyond exercise — although Patton made it clear that the workouts are hardly easy. It’s also become a support group of sorts for transplant patients.

“We get together on Saturday mornings in a park and do an exercise program,” Patton says, “but we also are talking about shared experiences.”

Patton got to show off her hard-won strength at her first Transplant Games of America in 2018. At the event in Salt Lake City, she competed in the 5K and 20K cycling races, 200-meter foot race, softball throw and doubles tennis. She won a silver medal in the 5K, bronze in the 20K and bronze in the 200-meter run.

“Training for me required, because I’m a stay-at-home mom, having Hattie with me, so I trained for many months with a mountain bike and the trailer attached,” Patton says. “I didn’t actually settle on my nice road bike until about a month before the event, and so when I got there, I was really inexperienced for the race, but the team was so awesome, and they asked me what I had been training with, and then I told them and they were like, ‘That’s awesome.’ Let’s see what happens out here on this course, and I ended up doing really well.”

The next year, she went to the World Transplant Games in Newcastle, England, where she competed in the 30K cycling race, singles golf and singles tennis, returning home to Austin with a silver medal in golf and a bronze in tennis.

And for the upcoming 2020 Transplant Games of America, Williams, Patton and five or six other heart transplant patients from around the Austin area plan to travel to the host city of Camden, New Jersey, together. Patton intends to compete in singles and doubles tennis, cycling and golf.

Although Patton says she’s always been active and enjoyed working out — she even at one time had ambitions of becoming a pilates instructor — her heart transplant has given her an entirely new perspective on the practice.

“When I go and I exercise now, there is a perspective of it that is not just for enjoyment, but it’s actually [that] I am caring for this beautiful gift I have been given,” she says. “I am doing the things to keep it healthy, but I am also incredibly grateful for it.”

“Exercise from a place of gratitude is very different for me than just, ‘I have to get to the gym today because I want to fit in those jeans,’ or whatever. It’s a different attitude and sentiment. I’m also much more forgiving of myself and my inadequacies. There’s grace that I give myself and my body.”

That’s one lesson we could all do well to learn from Patton. Another, she made a point to highlight for people to be proactive about their heart health — that just because you look a certain way, eat healthy and exercise regularly, doesn’t mean you’re completely in the clear when it comes to heart health.

“Heart disease kills more women every year than all cancers combined — my sisters and I lost our mother to a heart attack while I was in ICU,” Patton says. “On the surface, she seemed fine. She had an undiagnosed heart and thyroid disease. I’d like to save other families from this. Please learn your numbers — blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI and glucose. Track them. Get help if they are out of range. Love your beautiful, amazing heart.”