Kickin' It

They are the biggest muscles in our body. As such, our quadriceps and glutes require a lot of oxygen; probably the reason so many fitness swimmers and triathletes prefer not to use their legs. But, if you don’t use your legs, they can (and will) become your anchor. So what do you do? The answer: Learn to kick more efficiently.

If you’ve ever cracked a whip or used battle ropes before, you’ve seen how energy flows from the origin out the tail or toward the ends. Now imagine your legs are like two whips, with the origin being at the hips. The kicks are initiated from the hip flexors, with energy traveling down to the feet. Many swimmers actually think you shouldn’t bend at the knee, which is incorrect. This flow of energy means there is a bend in the knee.

While it’s beneficial to have a bend in the knees, it’s imperative that the kick comes from the core instead of from below the knees. In teaching this motion, I often ask my athletes to imagine kicking a soccer ball. When you kick a ball, you sort of “set up” the kick with a loading of the knee.

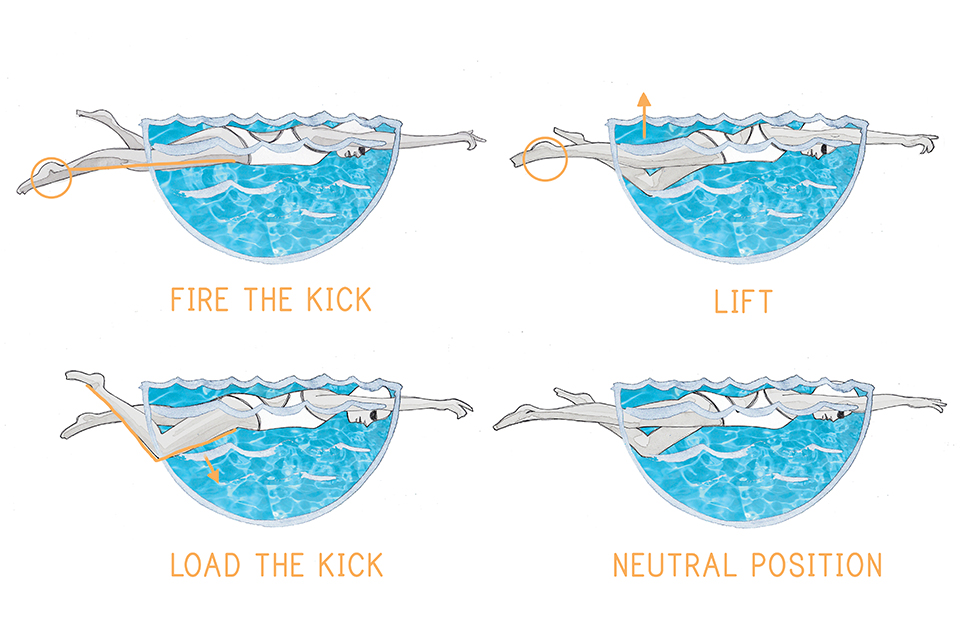

Loading or Setting Up the Kick

When lying on your stomach, the quads and knees will move slightly down and forward, creating a tighter angle.

Firing of the Kick

The kick is fired from your core and glutes to create a whip-like action through the legs with energy traveling out the toes both downward and slightly backward. Picture the laces on your tennis shoes. During the down kick, strive to feel the pressure where the laces would be—as if connecting with the soccer ball. Effective kicking engages hip flexors, glutes and quads on the down kick, and the hamstring and glutes on the upstroke of the kick. Just as when you connect with a soccer ball you “follow through,” you wouldn’t stop your forward momentum as soon as you connect with the ball. Instead, you would kick forward beyond the plane of your knee. The same is true when firing your flutter or dolphin kick; you aim to kick beyond or lower than the knee.

When kicking fluidly, the kick feels very cyclical:

Load the knee

Fire from the core and glutes

Lift the hamstring as the pointed toe is extending to make contact with the imaginary ball

Load the knee as the heel is just about to reach its highest point in the cycle

Common errors in swim kicks include:

Keeping the legs straight — Your leg becomes a very long lever, sans hinges, moving through the water. You will tire quickly and likely use bigger, less efficient kicks. These two outcomes will generally lead to sinking legs and then an uphill swimming stroke.

Kicking from the knees — This kick will be less efficient because you aren’t using your stronger leg muscles. Your feet will probably lift too high out of the water causing you to kick air more than water. Hint: that won’t help you move forward.

A dorsi flexed (toes pointed upward toward the shin) foot — Unfortunately, most fitness swimmers and triathletes don’t have the most flexible ankles and often swim with their toes leading the down beat and heel leading the upbeat. Instead, you should swim with your feet in a plantar flexed position (toes pointed) with the “shoe laces” leading the down beat and sole of foot leading the upbeat.

I encourage all my swimmers to practice kicking. At the very least, don’t let the kick weigh you down or create more frontal resistance. At best, strive to use the kick as forward propulsion. You’ll need to train your body to respond to the aerobic demands that kicking requires. But if you do, trust me: you will get faster!